Music Industry: So Bent, It's Straight

Former chief economist of Spotify- Will Page published a book last month which unravels how the economics behind the Music industry work

We write a daily newsletter on all things Music, and the Business and Tech behind it. If you’d like to get it directly in your inbox, subscribe now!

What’s good everyone?

Last month, the former chief economist of Spotify- Will Page, published a book called Tarzan Economics, which talks about how organizations pivot from the analog to the digital world, in the midst of a pandemic, and how they can take a cue from the music industry, on learning to let go of the ‘old vine’ and grab onto the ‘new vine’ of a digital-first approach.

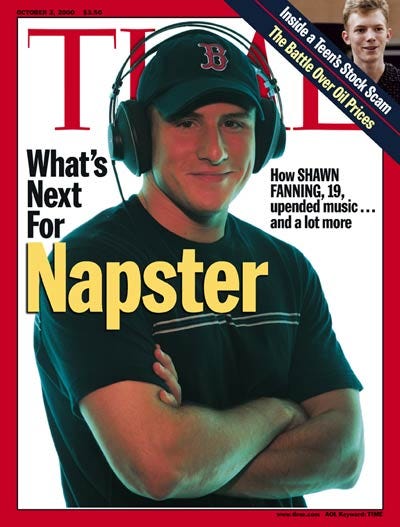

In what he calls the Napster moment for any industry: referring to the online P2P platform of sharing songs for free, which went viral in the early 2000s- at the dawn of the Internet era; Page talks passionately in his book about why organizations can learn from how the Music industry pivoted from two decades of suffering from piracy into a much better shape today, with the rise of legal music streaming apps such as Spotify.

However, before getting into that, Page first explains how the Music Industry finds itself in such a bad shape, to begin with, and why the economics between the artist and the end consumer is so complicated.

I myself am in the process of reading this book, and as part of this segment of Newsletters that I plan to write, called ‘So Bent, It’s Straight’, I will be sharing the key takeaways from my week’s reading.

The idea is to have you guys learn and participate along with me, instead of me blabbering on myself, and hopefully, we both can be wiser off by the end of the book.

If you feel this segment would be of interest to someone who would want to learn more about how the money behind Music and Entertainment works, share it with them now!

So, without further ado, let’s get right into it 👇🏻

Let’s Party like it’s 1999

In the very first chapter of the book, Page talks about the time, 20 years back, when CD sales were going through the roof, to such an extent, wherein, the record industry executives could weigh their profits on a physical scale (quite literally!)

So predictable was the demand for a Compact Disk, that it did not matter what was inside it, whether it was The Rolling Stones or a random alternative band, if a CD was sold, the record company would make a profit. As simple as that.

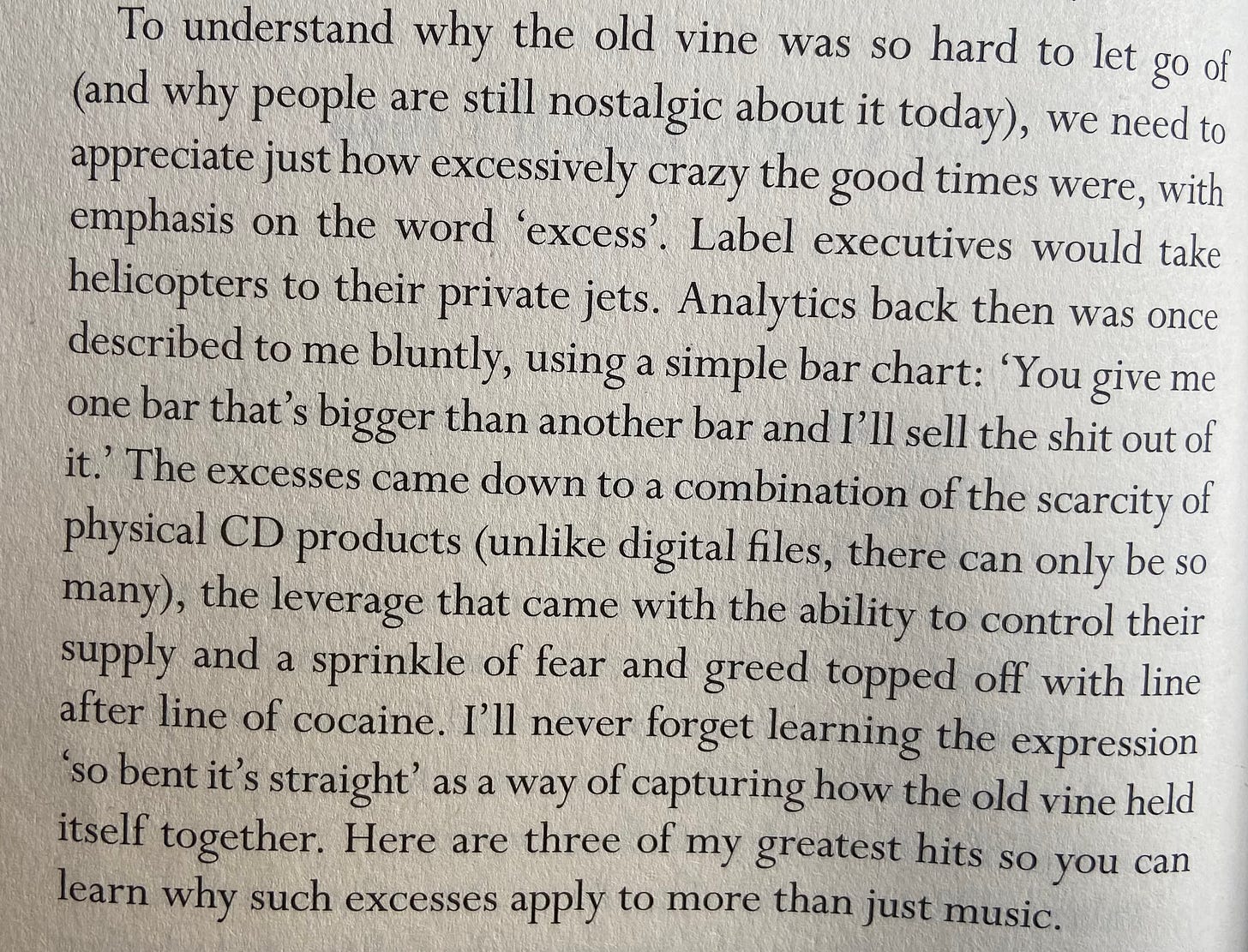

Such were the times, “back in the day”, that the global music recording industry was worth $60 Billion, after adjusting for inflation, almost 3x of what it is today. To get an idea of the kind of excesses in the industry, Page talks about it in his book ⬇️

So essentially, the fact that record label executives- fueled by cocaine and incredible leverage they held over the industry, could create artificial scarcity of CD’s, the only medium of consuming music, and end up skyrocketing the prices, ensured that it did not matter what was inside the CD, as long as it played music, the record company made money!

Can you imagine something like that today? 🤯

To further drive home his point, Page talks about 3 excesses or ‘scams’ that were rampant in the industry in the 90s. Let’s check one out here 👇🏻

📻The Payola

Record Labels paid ‘Independent’ Radio promoters to get their songs featured on the radio and get a buzz created around the same for its sales.

The keyword here is- ‘Independent’, as the promoter was neither an employee of the Record Label nor was he employed by the Radio Station. All this promoter used to do was act as a middleman between the two- without either of their knowledge. How?

The promoter would go to the radio station and pitch them a particular song and enquire about their intention to play it. If the station said something like:

“Sure, we love that record, we’re going to play it all day once it’s out”- that was all the promoter needed to know.

Next, he would go to the record label and say- “ If you lay out $20,000, I can get this to play on the top radio stations all day long”.

Why wouldn’t a label want that? The label agreed, the radio station got a cut of it for trading their insider information and the promoter?

Well, he made money for making something happen, which was inevitably going to happen.

The label paid to play what was already going to be played.

Sounds too easy right?

Guess what, it really was. All one needed was the right connections as an independent radio promoter and you could make money without distorting market forces.

In 2002, at the peak of the Payola scams, investigations by the office of then-New York District Attorney Eliot Spitzer uncovered evidence that executives at Sony BMG music labels had made deals with several large commercial radio chains.

Spitzer's office settled out of court with Sony BMG Music Entertainment in July 2005, Warner Music Group in November 2005, and Universal Music Group in May 2006. The three conglomerates agreed to pay $10 million, $5 million, and $12 million respectively to New York State non-profit organizations that will fund music education and appreciation programs.

The Music industry had dug a hole so deep for itself, there simply was no way out-and hence Page refers to this phenomenon of ‘So Bent, It’s Straight’ to illustrate how acceptable such scams had become.

What’re your thoughts on this? Leave a comment and let me know!

In the next edition of this series I will be talking about the other two types of rampant scams that Page talks about in his book in those times:

Chart Hyping 📈 & Album Certifications 🏆

Stay tuned 🤘🏻

If you liked this newsletter from Incentify, why not share it with someone you like?

P.S- Follow us on Instagram and Twitter for more such content on all things Music and Culture, now!