Why is listening to New Music so hard?

You decide to listen to a new album but 3 songs in, you realize you have not been paying attention and you instantly change the song to something you already like.

We write a daily newsletter on all things Music, and the Business and Tech behind it. If you’d like to get it directly in your inbox, subscribe now!

Hi Everyone,

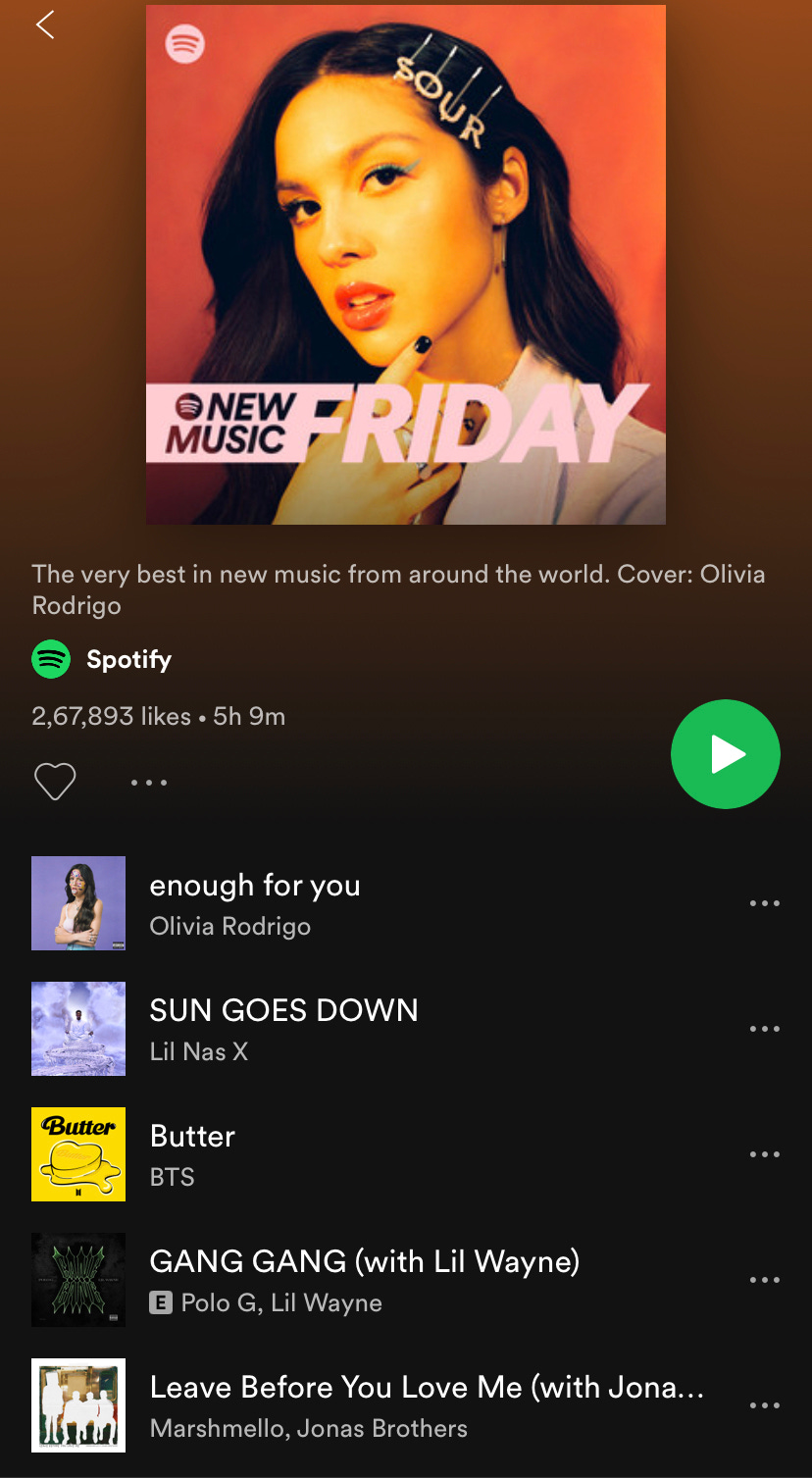

Last week, we covered how KPop band BTS’ new single ‘Butter’ was the fastest song in history to reach 100 Million views- in less than 24 hours, beating their own record with their previous single- ‘Dynamite’.

But did you actually listen to it? Or the 50 odd new songs added to the official charts last week?

Spotify reported earlier this year, that roughly 60,000 new songs are added EVERY DAY to their platform by various creators across countries- which means a new song is uploaded every 1.4 seconds to the streaming platform 🤯

But how many of these songs are actually consumed by its users? Or lost in oblivion, never being picked up by the algorithms, and suffer poor engagement rates compared to the already well-established classics. So why is it so tough to listen to new music?

It was a question that Coco Chanel- founder of fashion brand Chanel and the rest of the Parisian audience might have asked at the 1913 premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, an orchestral ballet-inspired by the Russian composer’s dream about a young girl dancing herself to death.

Stravinsky, having already thrilled Paris with his ferociously complex Firebird ballet three years earlier, was the bright young thing of symphonic music in Paris, and The Rite was to be something essentially unheard of.

When the lights finally drew down on the famous Théâtre des Champs-Élysées that evening, The Rite began with a solo bassoon squeezing out a riff so high in its register that it sounded like a broken English horn. This alien sound was—apparently and unintentionally—so strange that laughs erupted from the crowd in the theatre.

The opening gave way to the assault of the second movement, “The Augurs of Spring,” and the dancers—choreographed by the legendary Vaslav Nijinsky of the Ballets Russes—bounded on stage, moving squeamishly and at different angles. As recounted in various books and memoirs since, the laughs turned into jeers, then shouting, and soon the audience was whipped into such a frenzy that their cries drowned out the orchestra.

Many members of the audience could not fathom this new music; their brains to a certain extent- dead. A brawl ensued, vegetables were thrown, and 40 people were ejected from the theater. It was a fiasco consonant with Stravinsky’s full-bore attack on the received history of classical music, and thus, every delicate sense in the room.

“One literally could not, throughout the whole performance, hear the sound of music,” Gertrude Stein recalled in her memoir. The famous Italian opera composer Giacamo Puccini described the performance to the press as “sheer cacophony.” The critic for the daily newspaper Le Figaro noted that it was a piece of “laborious and puerile barbarity.”

Cut to the 21st Century,

The Rite of Spring is now hailed as the most sweepingly influential piece of music composed in the early 20th century and sowed the seeds of an entire outgrowth of modernism: jazz, experimental, and electronic music.

Maybe the Parisian audience wasn’t expecting a feat so unfamiliar and new that night, they simply wanted to hear music they recognized that drew upon the modes and rhythms they had come to know. Life was on one track, and suddenly they were thrust off into the unknown. Instead of a reliable ballet, many left the theater that night miserable, agitated, and for what, just to hear some new music?

But why blame the angry Parisian crowd that night? Aren’t we all the same? People love the stuff they already know. It’s something too obvious to dissect, a positive feedback loop- We love the things we know because we know them and therefore we love them.

However, there is a physiological explanation for our nostalgia and our desire to seek comfort in the familiar. It can help us understand why listening to new music is so hard, and why it can make us feel uneasy, angry, or even riotous.

It has to do with the plasticity of our brain. Our brains change as they recognize new patterns in the world, which is what makes brains useful. When it comes to hearing music, a network of nerves in the auditory cortex called the corticofugal network helps catalog the different patterns of music.

When a specific sound maps onto a pattern, our brain releases a corresponding amount of dopamine, the main chemical source of some of our most intense emotions. This is the essential reason why music triggers such powerful emotional reactions, and why, as an art form, it is so inextricably tied to our emotional responses.

Take the chorus of “Someone Like You” by Adele, a song that has one of the most recognizable chord progressions in popular music: I, V, vi IV. The majority of our brains have memorized this progression and know exactly what to expect when it comes around. When the corticofugal network registers that of “Someone Like You,” our brain releases just the right amount of dopamine. The more “records” we own, the more patterns we can recall to send out that perfect dopamine hit.

The essential joy of Music comes in how songs subtly toy with patterns in our brains, spiking the dopamine more and more without sending it off the charts. This is the entire neuroscientific marketing plan behind pop music, but when we hear something that hasn’t already been mapped onto the brain, the corticofugal network goes a bit haywire, and our brain releases too much dopamine as a response. When there is no anchor or no pattern on which to map, music registers as unpleasant, or in layman’s terms, bad.

The way the corticofugal system learns new patterns limits our experiences by making everything we already know far more pleasurable than everything we don’t. It’s not just the strange allure of the song your mother played when you were little or wanting to go back to that time in high school listening to the freshest hit in town. It’s that our brains actually fight against the unfamiliarity of life.

So why do artists still produce new music? Shouldn’t they simply resign to the fact that there are more than enough songs for everyone already made? What keeps them going?

The Youth. Young people remain the biggest consumers of new music and in this unfamiliar world of the pandemic, our brains have never been more plastic—a spongy tabula rasa onto which you can imprint a new timestamp. Another argument for constant music exploration is that we will assuredly remember these pandemic days, the way we remember our first breakup or first love, and the songs that defined them.

When we look at the majority of teenagers and young adults on social media platforms, they identify with a genre. Be it Indie or Hip Hop, the culture around music is a very big part of what urges them to get involved and feel as if they are part of a community. In a way, this has triggered a very experimental approach to music and the urge to communicate their personality using their taste in music.

We at Incentify run a “Song of the Day” series where we post new songs every day along with the backstory of the artist and the genre.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter & DM us your favorite artist/genre, we will get back to you with an exclusive story and personalized playlist on the same!

If you liked this newsletter from Incentify, why not share it with someone you like?